Assessing the terrain of Zimbabwean mbira performance in 1932, ethnomusicologist Hugh Tracey called the njari “by far the most widely spread variety in this country” (79). Yet the njari’s popularity declined over the coming decades, even as the mbira dzavadzimu experienced an apparent revival. Writing in 1963, for example, Andrew Tracey observed young men playing the mbira dzavadzimu in both rural and urban areas, even as he declared that “the njari appears to be played mainly by older men” (23). This trend continued, leading John Kaemmer to observe that by 1975 the njari was “a type of mbira which is not widely used today; at Madziwa the performers are old men who have not played regularly for several years” (86).

The njari in Guruve

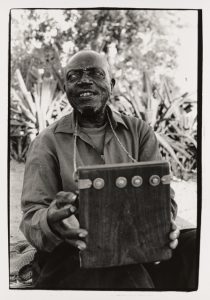

The njari was the first type of mbira that Sekuru Chigamba ever heard. Within his extended family, there were at least two njari players. Among them were his brother Fryson, who actively played njari until losing one of his thumbs in a car accident, as well as one of Sekuru Chigamba’s maternal grandfathers.

The brother to my grandfather, my mother’s father, he was playing njari. So when he used to play njari, I used to go and sit. But you know, I was laughing at him – “Why do you play these things? Why do you play mbira? And singing? No one asks you to sing, but you sing!” You know, in those days I was young. I loved his music. But you know, I didn’t want him to play alone. Just seated there playing, singing, with no other people watching him. So that’s what I didn’t want him to do. I wanted him to sing for people. But he said, “No, this is mbira. It’s music. You can play any time. Even when you are alone, you can play.”

The njari’s presumed distribution

Hugh Tracey has suggested that the njari was originally played by Nyungwe-speaking communities in the Zambezi Valley, likely near the Mozambican region of Tete. According to Tracey, the instrument traveled via Portuguese trade routes, reaching the Zimbabwean region of Buhera in the late 17th or early 18th century. traveled via Portuguese trade routes. Tracey has suggested that the njari had spread to areas within a hundred mile radius of Buhera by 1900, including “Mrewa, Rusapi, Bikita, ‘Victoria [Masvingo]’, Chibi, Chilimanzi and ‘Salisbury [Harare]’ districts” (1932: 89) By 1932, Tracey suggests that the njari had also spread to Mutoko. On the other hand, Tracey specifies that the njari was not played as far north as the Mount Darwin region. Furthermore, Andrew Tracey associates various types of njari with Nyungwe, Sena/Tonga, Njanja, Karanga, Hera, Bocha, Garwe, Manyika, Zezuru, Nohwe, Shangwe, and Chikunda speakers, but not with Korekore speaking communities (1972: 87).

Mapping the njari further north

Here, Sekuru Chigamba’s early experience with the njari appears to challenge established understandings of the instrument’s historic range. Indeed, Sekuru Chigamba asserts, “Njari was played all over Zimbabwe.” At the same time, he associates the instrument specifically with his home region of Guruve, which is located nearly 200 miles north of Buhera. Comparing the njari to the mbira dzavadzimu, he told me

If you go to Guruve, they were playing njari all along, but very few people were playing these. And we are still few, because it’s me, my brother, and a few other people there. They are very few who play this. But most of them, they know njari.

In addition to members of his own family, Sekuru Chigamba recalls hearing other njari players from Guruve in the early 1940s. These include a player named Chimanikire, who was featured on national radio broadcasts alongside other njari players, such as Simon Mashoko.